AI and Cubism – abstract lessons in discovery

Cubism was founded in the early 1900s, ripe with the context of a brewing world war. Amidst growing nationalist rhetoric and the rapid industrialisation of Germany, European states yearned for self-determination and accordingly, engaged in an accelerated process of militarisation. This fuelled suspicion and fear among allied countries, which the outbreak of WWI only exacerbated.

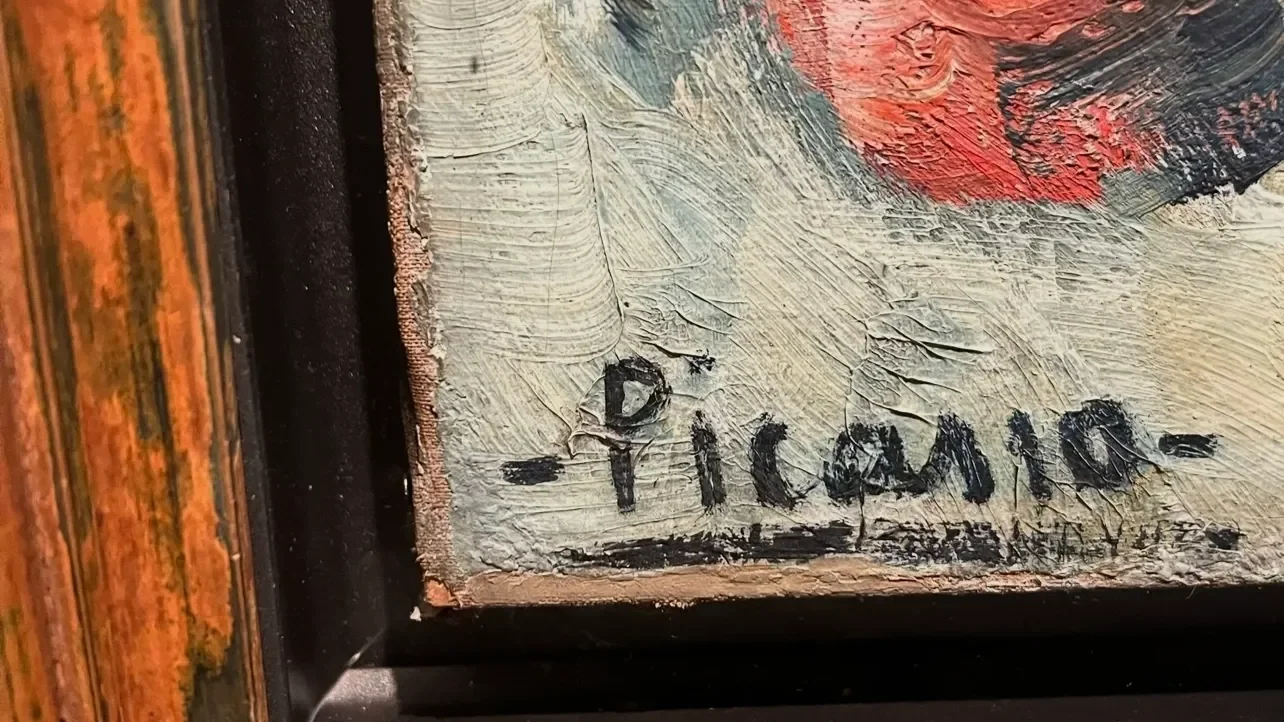

The aim of Cubism, laid bare by its developers like Picasso and Braque, was to abandon the constructed presentation of a ‘real’ subject by artists in their works and instead attempt what was previously considered impossible – to present every element of the subject. Present as many perspectives as it took to get as close as possible to the higher truth, and then communicate it; good or bad, beautiful, or ugly.

This line of thinking was exhilarating to view, like unleashing a level of consciousness to anyone who wanted it. Cubism was a lifeline, its raw truth a reflection of the veil undrawn upon the level of global destruction that modern capitalism and industrialisation were capable of. Never before were so many nations and their goals at odds with each other, all whilst expansion into mass innovation and industrialisation took place. At last, the allusive Pandora’s box of modernity in the new century was unveiled, for it had already riddled society with a form of sinister temptation. In a serendipitous form, Cubism’s unapologetic commitment to the expansion of the mind was revealed alongside said modernity.

Today, as the dominoes fall following the bullish release of AI into the world, we can’t even comprehend, on an immediate and mass scale, the long-term effects of it on our consciousness and its impact on our climate environment. It feels, again, like rapid innovation led by producers without permission. Its ability to permeate our day-to-day life so abruptly feels again like an exposed layer of consciousness to the human condition, one that feels more personal, more violent.

As the World Wide Web was introduced on a mass scale in the 1990s, companies and entrepreneurs were using it as a tool to promote their products and connect them with people, and people were using it to connect intimately and easily. Meanwhile, the developers of accessible AI were using its collective data to understand almost every aspect of how an individual thinks, much like a diary or a map to human enhancement, with endless entries. Whilst accessible generative AI (chatbots like ChatGPT and Gemini) has its limitations, it continues to improve rapidly. The data on the human condition that it holds seems infinite, and it’s all privately owned.

Like the concept of Cubism, AI holds a mirror to a previously unfathomable level of understanding of the world around us. We are suddenly acutely aware of (seemingly) every intimate and violent feature of our society, including the cannibalistic pursuit of innovation. Communities are already being affected by AI data centres and their waste output, just metres from their homes, as they seek personalised health advice online.

But like any discovery, the lasting effects of AI are unknown. Maybe it will, like the internet, help our collective development with the right regulation and monitoring. Eventually, after the rubble clears, it could make people more equal across social classes (as Mo Gawdat hypothesises), allowing us time for hobbies and love. However, until we can genuinely rest easy with the thought of using AI and technological innovation at a level beyond what we have ever known, perhaps we can utilise consciousness-building tools like consuming the mind-bending and exhilarating art of Picasso and Braque to nourish our souls and inspire the self-anchoring agency found in creation. Ultimately, that is at the heart of the human condition: our animalistic instinct to create and make sense of it all.